Let's talk about... trends

What are they? Where do they come from? And why is 'Bookshelf Wealth' so much more interesting than 'Unexpected Red'...

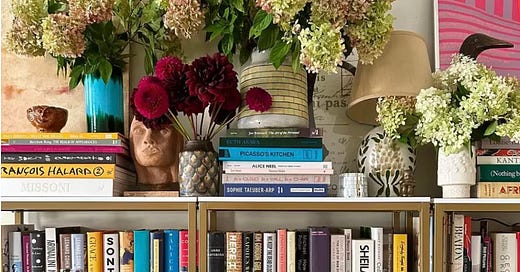

Newspaper journalists are often keen for a quote on "the-latest-trends”. What do I think of polka dots? What about red, hot right now, non? It depends. Or most recently... what could I say about the latest on TikTok: ‘Bookshelf Wealth’. Hmmm, interesting.

Obviously, just because images of a lot of spotty things have been cobbled together by someone on Instagram, or an influencer declares in breathless tones that poppy has surpassed magnolia in the paint stakes, does not make it universally true. But this is not to flagellate the notion of ‘trends’ per se. The stylistic movements which visualise our cultural climate can be genuinely intriguing. However, here-today-over-tomorrow fads can be noxious, creating false needs and unnecessary consumption. But I’ll come back to the bookshelves.

The thing is, true trends don’t occur in a vacuum, you can always trace their roots. In short, no roots = no relevance = fad. In contrast, the creativity which reflects, and responds to, the context of contemporary life — as determined by politics, the economy, ecological issues, international affairs — inevitably impacts the recognised mainstream arbiters of style: art, fashion, design, and cinema. These key ‘influencers’ (of the authentic kind) have a heavy hand in defining the zeitgeist which ultimately trickles down to the mainstream whereupon we’re all affected (what becomes easily available to appreciate, wear, buy or watch).

True trends also always answer a need. Emerging from an alchemy of desire, available resources, and cultural resonance, they have the power to make visible unspoken truths.

However, while a trend may mark the beginning of a new direction, in and of itself, a trend is not a new form of expression. That honour belongs only to the ‘genius’ originator aka the person capable of having a seemingly good idea not in general circulation. That someone else picked up on it, and collated an array of evidence to support the proposition, is not creativity but editing. Whether this subsequently falls into the collective consciousness, ergo the reaching of a tipping point, depends entirely on the socioeconomic context. In other words, are enough other people either feeling the same pain or subject to the same influences to care?

But, as Kurt Vonnegut wrote, "A genius working alone is invariably ignored as a lunatic." Instead, the maverick originator must, as author Malcolm Gladwell referred to in his book The Tipping Point: How little Things Can Make a Big Difference, rely on a system of Connectors, Mavens and Salesmen. The former are people with large social networks across an array of circles who link people together; the latter are the persuaders, the charismatic orators who win arguments. While the mavens are the research nerds, what Gladwell calls the "people we rely upon to connect us with new information." When this holy trinity gets behind an idea, it has the capacity to spread like a virus.

Alternatively, it's called marketing. Because someone somewhere will make money